Some words are satisfied spending an evening at home, alone, eating ice-cream right out of the box, watching Seinfeld re-runs on TV, or reading a good book. Others aren't happy unless they're out on the town, mixing it up with other words; they're joiners and they just can't help themselves. A conjunction is a joiner, a word that connects (conjoins) parts of a sentence.

The simple, little conjunctions are called coordinating conjunctions (you can click on the words to see specific descriptions of each one):

| Coordinating Conjunctions | ||||||

| and | but | or | yet | for | nor | so |

(It may help you remember these conjunctions by recalling that they all have fewer than four letters. Also, remember the acronym FANBOYS: For-And-Nor-But-Or-Yet-So. Be careful of the words then and now; neither is a coordinating conjunction, so what we say about coordinating conjunctions' roles in a sentence and punctuation does not apply to those two words.)

When a coordinating conjunction connects two independent clauses, it is often (but not always) accompanied by a comma:

When the two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction are nicely balanced or brief, many writers will omit the comma:

The comma is always correct when used to separate two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction. See Punctuation Between Two Independent Clauses for further help.

A comma is also correct when and is used to attach the last item of a serial list, although many writers (especially in newspapers) will omit that final comma:

When a coordinating conjunction is used to connect all the elements in a series, a comma is not used:

A comma is also used with but when expressing a contrast:

In most of their other roles as joiners (other than joining independent clauses, that is), coordinating conjunctions can join two sentence elements without the help of a comma.

Beginning a Sentence with And or But |

A frequently asked question about conjunctions is whether and or but can be used at the beginning of a sentence. This is what R.W. Burchfield has to say about this use of and: There is a persistent belief that it is improper to begin a sentence with And, but this prohibition has been cheerfully ignored by standard authors from Anglo-Saxon times onwards. An initial And is a useful aid to writers as the narrative continues. The same is true with the conjunction but. A sentence beginning with and or but will tend to draw attention to itself and its transitional function. Writers should examine such sentences with two questions in mind: (1) would the sentence and paragraph function just as well without the initial conjunction? (2) should the sentence in question be connected to the previous sentence? If the initial conjunction still seems appropriate, use it. |

Among the coordinating conjunctions, the most common, of course, are and, but, and or. It might be helpful to explore the uses of these three little words. The examples below by no means exhaust the possible meanings of these conjunctions.

ANDAuthority used for this section on the uses of and, but, and or: A University Grammar of English by Randolph Quirk and Sidney Greenbaum. Longman Group: Essex, England. 1993. Used with permission. Examples our own.

The Others . . .The conjunction NOR is not extinct, but it is not used nearly as often as the other conjunctions, so it might feel a bit odd when nor does come up in conversation or writing. Its most common use is as the little brother in the correlative pair, neither-nor (see below):

>It can be used with other negative expressions:

It is possible to use nor without a preceding negative element, but it is unusual and, to an extent, rather stuffy:

The word YET functions sometimes as an adverb and has several meanings: in addition ("yet another cause of trouble" or "a simple yet noble woman"), even ("yet more expensive"), still ("he is yet a novice"), eventually ("they may yet win"), and so soon as now ("he's not here yet"). It also functions as a coordinating conjunction meaning something like "nevertheless" or "but." The word yet seems to carry an element of distinctiveness that but can seldom register.

In sentences such as the second one, above, the pronoun subject of the second clause ("they," in this case) is often left out. When that happens, the comma preceding the conjunction might also disappear: "The visitors complained loudly yet continued to play golf every day."

Yet is sometimes combined with other conjunctions, but or and. It would not be unusual to see and yet in sentences like the ones above. This usage is acceptable.

The word FOR is most often used as a preposition, of course, but it does serve, on rare occasions, as a coordinating conjunction. Some people regard the conjunction for as rather highfalutin and literary, and it does tend to add a bit of weightiness to the text. Beginning a sentence with the conjunction "for" is probably not a good idea, except when you're singing "For he's a jolly good fellow. "For" has serious sequential implications and in its use the order of thoughts is more important than it is, say, with because or since. Its function is to introduce the reason for the preceding clause:

Be careful of the conjunction SO. Sometimes it can connect two independent clauses along with a comma, but sometimes it can't. For instance, in this sentence,

where the word so means "as well" or "in addition," most careful writers would use a semicolon between the two independent clauses. In the following sentence, where so is acting like a minor-league "therefore," the conjunction and the comma are adequate to the task:

Sometimes, at the beginning of a sentence, so will act as a kind of summing up device or transition, and when it does, it is often set off from the rest of the sentence with a comma:

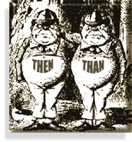

The Case of Then and Than |

In some parts of the United States, we are told, then and than not only look alike, they sound alike. Like a teacher with twins in her classroom, you need to be able to distinguish between these two words; otherwise, they'll become mischievous. They are often used and they should be used for the right purposes. Generally, the only question about than arises when we have to decide whether the word is being used as a conjunction or as a preposition. If it's a preposition (and Merriam-Webster's dictionary provides for this usage), then the word that follows it should be in the object form.

Most careful writers, however, will insist that than be used as a conjunction; it's as if part of the clause introduced by than has been left out:

In formal, academic text, you should probably use than as a conjunction and follow it with the subject form of a pronoun (where a pronoun is appropriate). Then is a conjunction, but it is not one of the little conjunctions listed at the top of this page. We can use the FANBOYS conjunctions to connect two independent clauses; usually, they will be accompanied (preceded) by a comma. Too many students think that then works the same way: "Caesar invaded Gaul, then he turned his attention to England." You can tell the difference between then and a coordinating conjunction by trying to move the word around in the sentence. We can write "he then turned his attention to England"; "he turned his attention, then, to England"; he turned his attention to England then." The word can move around within the clause. Try that with a conjunction, and you will quickly see that the conjunction cannot move around. "Caesar invaded Gaul, and then he turned his attention to England." The word and is stuck exactly there and cannot move like then, which is more like an adverbial conjunction (or conjunctive adverb — see below) than a coordinating conjunction. Our original sentence in this paragraph — "Caesar invaded Gaul, then he turned his attention to England" — is a comma splice, a faulty sentence construction in which a comma tries to hold together two independent clauses all by itself: the comma needs a coordinating conjunction to help out, and the word then simply doesn't work that way. |

A Subordinating Conjunction (sometimes called a dependent word or subordinator) comes at the beginning of a Subordinate (or Dependent) Clause and establishes the relationship between the dependent clause and the rest of the sentence. It also turns the clause into something that depends on the rest of the sentence for its meaning.

Notice that some of the subordinating conjunctions in the table below — after, before, since — are also prepositions, but as subordinators they are being used to introduce a clause and to subordinate the following clause to the independent element in the sentence.

Common Subordinating Conjunctions | ||

|

after although as as if as long as as though because before even if even though |

if if only in order that now that once rather than since so that than that |

though till unless until when whenever where whereas wherever while |

The Case of Like and As |

Strictly speaking, the word like is a preposition, not a conjunction. It can, therefore, be used to introduce a prepositional phrase ("My brother is tall like my father"), but it should not be used to introduce a clause ("My brother can't play the piano

In formal, academic text, it's a good idea to reserve the use of like for situations in which similarities are being pointed out:

However, when you are listing things that have similarities, such as is probably more suitable:

|

Omitting That |

The word that is used as a conjunction to connect a subordinate clause to a preceding verb. In this construction that is sometimes called the "expletive that." Indeed, the word is often omitted to good effect, but the very fact of easy omission causes some editors to take out the red pen and strike out the conjunction that wherever it appears. In the following sentences, we can happily omit the that (or keep it, depending on how the sentence sounds to us):

Sometimes omitting the that creates a break in the flow of a sentence, a break that can be adequately bridged with the use of a comma:

As a general rule, if the sentence feels just as good without the that, if no ambiguity results from its omission, if the sentence is more efficient or elegant without it, then we can safely omit the that. Theodore Bernstein lists three conditions in which we should maintain the conjunction that:

Authority for this section: Dos, Don'ts & Maybes of English Usage by Theodore Bernstein. Gramercy Books: New York. 1999. p. 217. Examples our own. |

Beginning a Sentence with Because |

Somehow, the notion that one should not begin a sentence with the subordinating conjunction because retains a mysterious grip on people's sense of writing proprieties. This might come about because a sentence that begins with because could well end up a fragment if one is not careful to follow up the "because clause" with an independent clause.

When the "because clause" is properly subordinated to another idea (regardless of the position of the clause in the sentence), there is absolutely nothing wrong with it:

|

Some conjunctions combine with other words to form what are called correlative conjunctions. They always travel in pairs, joining various sentence elements that should be treated as grammatically equal.

Correlative conjunctions sometimes create problems in parallel form. Click HERE for help with those problems. Here is a brief list of common correlative conjunctions.

| both . . . and not only . . . but also not . . . but either . . . or |

neither . . . nor whether . . . or as . . . as |

The conjunctive adverbs such as however, moreover, nevertheless, consequently, as a result are used to create complex relationships between ideas. Refer to the section on Coherence: Transitions Between Ideas for an extensive list of conjunctive adverbs categorized according to their various uses and for some advice on their application within sentences (including punctuation issues).